Poisoning the well

This story was originally published at Searchlight New Mexico, a NMPBS partner.

Driving along a stretch of New Mexico Highway 605, just north of the tiny Village of Milan, it’s easy to imagine that this area has always been no-man’s-land. Little appears in the distance except for a smattering of homes and trees peppered by expanses of bone-dry scrub brush. But a hard second look reveals something else — vestiges of a mass departure. Sidewalks lead to nowhere, a dog house sits in the middle of a field next to a mound of cinder blocks, phone lines crisscross empty stretches of land and deserted propane tanks and mailboxes sit perched in front of nothing. Around the bend on one unpaved side road, a neighborhood watch sign stands sentinel where a neighborhood no longer exists.

John Boomer and his partner, Maggie Billiman, roam around a peeling concrete pad, pointing out the location of their old bedroom, art studio and kitchen. As she stands in one corner of what was once a 7,200-square-foot warehouse-turned-home, Billiman describes how she and John would pray to the east as the sun came up behind Mount Taylor, one of four sacred mountains to the Navajo. Billiman then pulls up a sickly looking ear of purple corn that has sprouted in a cement crack, the product of an errant seed blown over from one of the garden beds the couple planted years earlier.

“Do you think it’s safe to plant?” Billiman asks Boomer, referring to the legacy of groundwater contamination caused by a colossal pile of uranium mill waste that still looms in the distance, which is the reason why the couple recently left. He shrugs. “We can try.”

This home site was once part of a cluster of five rural subdivisions interspersed with rich farm and ranchland. The Homestake Mining Company — famously known for gold mining in the Black Hills of South Dakota — took up residence here in 1958, to mill uranium. From that year until 1990, millions of tons of ore were prised from nearby mines and processed at Homestake, where the ore was ground into fine particles and leached with a solution that coaxed out pure uranium oxide, often called “yellowcake.” That uranium was then shipped off to help make America’s Cold War fleet of nuclear weapons or to power nuclear reactors. The leftover slurry was piped into two unlined earthen pits, the largest the size of 50 football fields and filled with over 21 million tons of uranium mill tailings.

Over time, the uranium tailings decayed into radon gas; meanwhile, radioactive contaminants seeped into four of the region’s aquifers. Residents compiled a list of neighbors who died of cancer — they called it the Death Map. In 2014, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) predicted that the probability of developing cancer was notably higher for residents who lived closest to the mill, especially if they drank the water.

In the intervening decades, Homestake attempted to hold its remaining contamination at bay rather than offer a long-term solution. That changed in 2020, when the company declared that a full cleanup of the groundwater was not feasible and instead embarked on a mass buyout and demolition of homes inside the rural subdivisions and beyond, Boomer and Billiman’s included. Homestake’s goal, ultimately, is to hand over 6,100 acres of land — almost twice the size of nearby Milan — to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) as part of a special federal program that takes over shuttered nuclear outfits when industry walks away. The deadline is 2035. And if this site is anything like the majority of the DOE’s other sites, the land will be rendered inaccessible to the public, with the company’s guarantee that toxins will stay inside the massive contamination zone boundary for a thousand years.

“Talk about the myth of containment,” says Christine Lowery, a commissioner in Cibola County. “The myth of reclamation as well,” she adds. For Lowery, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna who lives in Paguate, one of its six villages — itself blighted by the Jackpile-Paguate Uranium Mine, one of the world’s largest open pit uranium mines — the subtext is clear. “What they should be saying is, ‘We’ve contaminated everything we can, and there’s no way we can fix it.’”

In fact, the conditions necessary for contaminants to infiltrate a fifth aquifer in a single generation — not a thousand years — could already be in the making. The aquifer in question is the San Andres-Glorieta, so ancient that its limestone was forged from the same material as seashells before the era of the dinosaurs. It’s also the last clean source of groundwater for Milan, the county seat of Grants, many private well owners and the Pueblo of Laguna, as well as the Pueblo of Acoma, one of the longest continually inhabited communities in the United States.

According to regulators, the San Andres-Glorieta still meets standards for groundwater that is safe to use and drink. According to Homestake’s own reports, however, at least three uranium plumes are converging toward what Ann Maest, an aqueous geochemist with Buka Environmental, a Colorado-based firm, calls “a bull’s-eye of radioactive contamination.” The potential target? A geological formation called a subcrop. Here, approximately 100 feet below the surface of the earth and three miles southwest of the Homestake site, this subcrop directly connects the San Andres-Glorieta with an overlying aquifer long known to transport contamination from two uranium mills including Homestake. In 2022, the company commissioned an independent firm to study the geological feature. But according to a memo sent to state and federal regulators and written by Maest the following year, the findings were “light on interpretation” and evaded answering the most important question of all: Have those contaminants reached the San Andres-Glorieta?

Homestake’s answer is no. In an email sent to Searchlight New Mexico, Brad Bingham, who manages the company’s mine-closure effort, said that company analysis “demonstrates that the [San Andres-Glorieta] has not been impacted by the Homestake site.” The company, he added, monitors wells both on- and off-site, and the data is made available in annual reports.

Gauging the extent of groundwater plumes is notoriously difficult. Topography and geology shape how groundwater moves, and sampling can underestimate the full range of a plume, leaving gaps in the data, whether that’s inadvertent or intentional. A 2022 ProPublica investigation found that regulators had been lax in their oversight of the Homestake mill, its toxic footprint and the uranium industry as a whole. Over time, a dizzying array of state and federal agencies have each overseen a different aspect of the site’s reclamation; in the past, those agencies haven’t even agreed on what that reclamation should look like.

Now, as uranium mining undergoes a national revival under initiatives that favor carbon-free nuclear energy, waste from the previous Cold War era of mining and milling endures. Homestake’s remediation — which has gone on for 49 years — exemplifies this legacy. During that time, company reports say, its collection wells have pumped out billions of gallons of contaminated water. Nearly one million pounds of uranium have been removed from the groundwater, too. Bingham says this represents 85 percent of the total uranium that was released into the environment. That’s in addition to the removal of tens of thousands of pounds of selenium and over a million pounds of molybdenum.

The company has attempted to keep pollutants that have seeped into groundwater from migrating farther away from the source. But this so-called hydraulic barrier has only addressed the symptoms of the contamination, not the cause: the tailings piles, which the company declined to relocate into a lined repository nearby. That means that some groundwater contamination continues to spread beyond Homestake’s site. The hydraulic barrier has another drawback — it has used “a massive amount of freshwater from the San Andres-Glorieta aquifer to operate,” says Laura Watchempino, a member of the Multicultural Alliance for a Safe Environment (MASE), a grassroots network of uranium-impacted communities working collectively to address the legacy of mining and milling on the health and environment of future generations. Watchempino is a former lawyer who also worked as a water quality specialist for the Pueblo of Acoma.

Flawed as the barrier is, critics are quick to emphasize that it has to remain in the face of the alternative — nothing at all. Still, as the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) confirmed, any long-term remediation measures that Homestake operated, including this barrier, will come to a halt once the site is handed over to the federal government. In 2021, the New Mexico Environment Department issued a clear warning on this point: Bringing an end to remediation activities, especially ones involving the hydraulic barrier, “could have dire consequences for the remaining potable water sources in the region.”

“I’m 85 and it all started when I was 40”

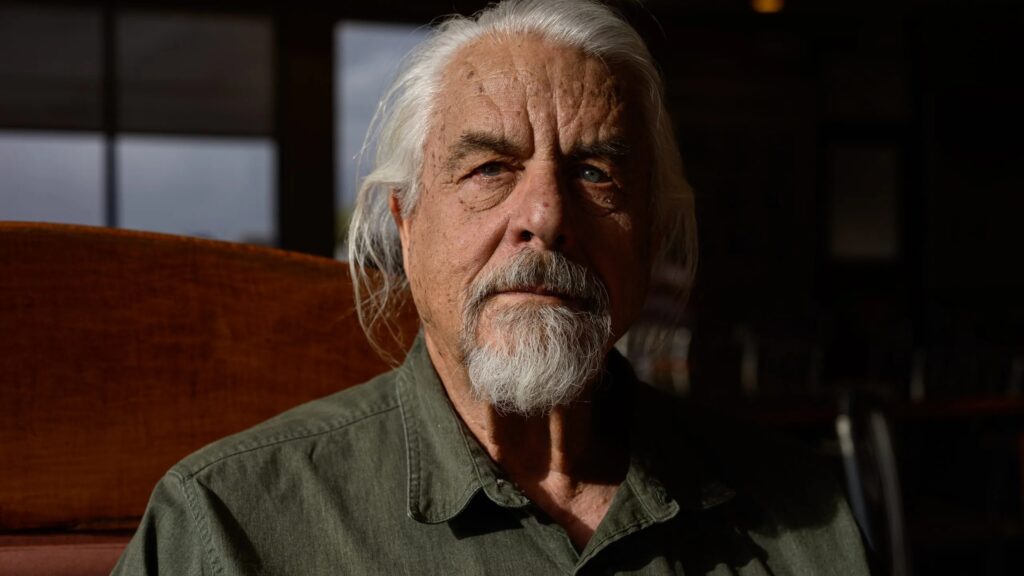

Sitting in his office on Uranium Avenue in Milan, surrounded by haphazard stacks of paper, binders and books, Larry Carver talks about the earliest years of his family’s presence in the region. His uncle on his mother’s side homesteaded a section of land when the area was nothing but rows of potatoes and carrots. “Some of the best farmland in the valley,” Carver says. His in-laws moved to Murray Acres, at the time a newly minted subdivision, in 1955. Carver followed in 1964 and bought five acres. His son and grandson are the third and fourth generations to live here.

Carver estimates that he is one of around 30 holdouts left in the five subdivisions; four of the families live in his own, Murray Acres. But few others have spent so much time fighting to hold the company accountable. “I’m 85 and it all started when I was 40,” he says.

In 1983, he was one of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit filed against the company, which argued, among other claims, that contamination of the well water had “completely destroyed the market value of the plaintiffs’ properties.” As part of the settlement, the company made small cash payments to residents and hooked them up to the municipal water system, which drew from the last clean source of water in the region, the San Andres-Glorieta. That year, the mill was designated a Superfund site, and in 1987 the company entered into a consent order with the EPA to analyze radon levels in residents’ homes, the product of uranium decaying from the tailings piles.

The mill closed in 1990, less than a decade after the uranium industry went bust. Records from the county assessor’s office show that Homestake quietly began buying a handful of homes in adjacent neighborhoods as early as 1996. (In 2001, Homestake Mining merged with the Canadian juggernaut, Barrick Gold, one of the world’s largest gold mining companies.)

“Every time someone dies or decides to move away, Homestake-Barrick Gold buys the property at a greatly reduced cost, which they can do because their ineffective groundwater remediation has devalued property many of us worked lifetimes to build,” Candace Head-Dylla, a former resident, said in a 2017 letter to the NRC.

In 2020, the company argued that it was no longer technically practical to clean up the groundwater to match its pre-mill days, Bingham wrote. So began the tangled regulatory process of applying for a less-stringent cleanup standard through the NRC, which first required Homestake to show that such a standard wouldn’t harm people or the environment. Homestake had to begin making what Bingham called “good faith offers” on homes as part of its NRC application. According to Ron Linton, a project manager with the NRC, the company has “an obligation to secure the land needed to safely isolate the mill tailings,” essentially clearing it of all human presence. Only then can the DOE move in as the contamination zone’s long-term steward.

Searchlight asked the DOE for comment, but the agency declined. According to Samah Shaiq, a former DOE spokesperson, the agency is not yet responsible for the site.

The NRC denied Homestake’s application for the lower standard — the basis of the buyout — but the company remains steadfast in its desire to walk away. As part of those plans, Homestake has already scooped up approximately 455 of the estimated 523 properties that sit inside its proposed boundary, an expanse that’s nearly as large as the most contaminated area of the Rocky Flats Plant, another of the more than 100 sites under the DOE’s perpetual care, where thousands of plutonium bomb cores for the nation’s nuclear arsenal were fabricated between 1952 and 1989.

Much of Milan, along with huge swaths of land west and north, including some five miles of Highway 605, sit within this massive pie-shaped chunk, a proposed boundary that is based on the company’s groundwater modeling data. Inside are public water and electric lines, groundwater wells, septic systems and other, smaller roads, the fate of which have yet to be determined. Milan Elementary School sits only a mile away from the boundary’s southernmost rim.

When Searchlight asked how fast those plumes are migrating, drawing on a Homestake-produced simulation that’s meant to predict how contaminants move in groundwater aquifers at the site, the EPA declined to comment, because the simulation was still in draft form.

Regulators, meanwhile, are plodding through the process of determining what final act of remediation they should require before allowing Homestake to hand off the site to the DOE. But prospects for that remedy depend on whether and when the company will receive a lower cleanup threshold. If a lower standard is settled on, that remedy, whatever it may be, will fall radically short of truly protecting groundwater, advocates believe. Adding to the uncertainty is a recent announcement that the Trump administration intends to cut personnel at the EPA by up to 65 percent.

The future of the site seems all but predetermined: a wasteland in the truest sense, and a national sacrifice zone. The buyout, a prologue to this future, has fractured residents’ lives in the present. Homestake subjected sellers to nondisclosure agreements — “standard business practice,” in Bingham’s words — but to some in the community, a mechanism for silencing dissent.

Homestake later ended that requirement based on community input, Bingham says. But according to Susan Gordon, MASE’s coordinator, the company was also known to make ultimatums to residents. One of them? Sell now or lose your property to eminent domain, she recalls locals telling her. By Bingham’s count, Homestake has already demolished 41 of those properties. And, as if to make the most of the current state of regulatory limbo, it has also rented two existing properties to local law enforcement officers, four to local community members and seven to its own employees.

Besides that, around fifteen families who sold their homes to Homestake rent their old properties back from the company, according to Bingham, who says the number can fluctuate at any given time. The agreements, he adds, came at the request of sellers who wanted to “determine their time of departure.” But the answer is more complicated, Gordon believes: Residents couldn’t find or afford comparable alternatives and families felt pressured to take buyouts that may not have been at market value while they sought other housing. Those owners-turned-renters are under strict leases with Homestake (one such lease is in effect for five years).

The company proposed buying Larry Carver’s home and then leasing it back to him as it had with others, Carver says, but the logic didn’t compute. “Why should I sell it to you and you tell me what to do when I can already do what I want today?” Then, in late February, Carver received a certified letter with an offer for his home and property based on a “drive-by appraisal.” The company gave him 30 days to respond; Carver plans to consult a lawyer.

John Boomer, who moved into the neighborhood in early 2001, says he “felt kind of naive looking back.” When he bought his home, EPA reports gave him the impression that the site would get cleaned up in a matter of years. But as time went on, he steadily lost faith in the company, which would “fudge and mislead the public,” he says. At one point, a clamp that held two pipes together disconnected on Homestake’s property, sending 27,000 gallons of water about 200 yards away from Boomer’s kitchen window. The NRC reported there was no risk to residents, but Boomer now characterizes the response as not only typical, but also “dismissive of the public’s concern and protective of the mining industry and the company.”

In 2010, the EPA mapped the levels of radioactive contamination in the windblown sand that drifted onto his property, later releasing three different maps with contradictory information, he recalls. The original map showed higher levels of contamination, but in the second and third maps, he says, the background levels — or the thresholds for what would be considered safe — had been changed to make his land look less polluted.

He finally decided to sell in 2022, but couldn’t find anything that matched the property he had in Milan, an old warehouse he’d spent years retrofitting into a home and art studio. He eventually settled on a place in San Rafael, a community 10 miles south, after a search that took almost seven months. The process exacted a toll on his physical and mental health, says Maggie Billiman, Boomer’s partner. It took Homestake several more months after the move to pay the promised $2,500 for his water rights, he adds. The well was supposed to be plugged as part of the deal, but when he shows me the well, it’s unclear whether the company has done anything at all.

“We’ve been poisoned to the gills”

The Grants Mining District stretches from the Pueblo of Laguna to Gallup, across almost 100 miles of western New Mexico’s red bluffs. Uranium here and throughout the world is ancient even by cosmic standards. Billions of years ago, exploding stars sent the element into our solar system and eventually into Earth’s crust. Around 1950, Paddy Martinez, a Navajo sheep herder, discovered the first commercially viable deposits in this region, just as the Cold War had started ratcheting up. Within five years, demand went from zero to tens of millions of pounds per year.

In time, more than 150 mines would be developed across this district and the greater San Mateo Creek Basin, and, today, there are a total of 261 former uranium mines statewide, making New Mexico the fourth-largest producer of uranium globally, behind East Germany, the Athabasca Basin and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which supplied much of the uranium for the Manhattan Project.

But with the uranium boom came a wave of devastation across the greater Southwest, including in Indigenous communities like the Pueblo of Laguna, as well as the Navajo Nation, where there are more than 500 abandoned uranium mines. Workers often lived near mines and mills and would bring yellowcake home on their clothes, exposing their families to harmful radioactive dust; water sources, meanwhile, have shown “elevated levels of radiation,” according to the EPA.

In the Church Rock Chapter of the Navajo Nation, a tailings dam breached on an early July morning in 1979, sending contaminated water into the Rio Puerco. Today, it constitutes the largest release of nuclear materials in the U.S. worse even than the meltdown at Three Mile Island.

Church Rock was among the eight mills that processed uranium ore in New Mexico. Others include Homestake and, in its immediate vicinity, Bluewater and two mills at Ambrosia Lake. Workers flocked here from across the state and nation during the booming 1960s and 1970s, with Homestake alone employing 1,500 people at its peak.

After graduating from high school and intermittently through his college years, Carver worked stints at all four of those mills before opening his own business, Carver Oil. At Homestake, he worked at a site where yellowcake was processed and packaged into barrels to go to Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where it would be enriched for use in nuclear weapons. He also worked in the tailings piles.

Carver now receives benefits for spots on his lungs from the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), a program he qualified for because of his time working in the mills. Whether his illness was compounded by living near the mill tailings and by breathing excess radon, or by drinking the water — at least until the company connected residents to a clean source — is unknown. Studies have shown that chronic exposure to uranium through drinking water can cause kidney damage and cardiovascular disease. When inhaled, uranium can lead to lung cancer and pulmonary fibrosis, a scarring of the lung tissue. Studies of uranium miners associate cumulative exposure to radon with higher rates of death by lung cancer.

Maggie Billiman, who’s from the Sawmill Chapter of the Navajo Nation, has advocated for RECA to cover people in New Mexico and parts of Arizona who lived downwind of atmospheric nuclear tests or who worked in mines after 1971, the current cutoff date. Last fall, she traveled with other Indigenous activists to Washington, D.C., as part of her efforts to expand RECA after struggling with various undiagnosed illnesses for years; several painful cysts that have yet to be biopsied were recently found on her liver and pancreas. Many doctor visits later, she’s still pursuing a clear diagnosis and treatment plan.

But whether or how one gets sick can depend on biological sex, age when exposed and the pathway a certain type of radioactive particle takes to enter the body. Proving that one’s illness originated as a result of living near a mine or mill, as opposed to actually working in it, is nearly impossible, given that symptoms can take years to manifest — a lack of clear causation that is ultimately advantageous to polluters.

Groundwater contamination from uranium mining was detected as early as 1961. Even before that, the federal government was aware that New Mexico’s waterways were already showing signs of radioactive contamination from the burgeoning uranium extraction industry. It would take another 15 years for Homestake to begin a convoluted, if limited, remediation effort: A series of collection wells would pull contaminated water out and treat it, then pump that water, along with clean water sourced from the San Andres-Glorieta, back into the subsurface.

This hydraulic barrier has come to have two functions. First, it pushes highly irradiated uranium and other toxic waste back toward the tailings piles. Second, as the NMED described it, it acts as a “plug in the bottom of a funnel that holds impacted groundwater from decades of mining and milling discharges in the [San Mateo Creek Basin].” This has never been a perfect solution, nor does it appear to have been designed for permanency. But, without it, the picture looks grim.

Homestake’s hydraulic barrier has mostly kept the tailings contained, but at the high cost of precious clean water. Homestake estimates that it’s used around 14 billion gallons since 1977 to operate this barrier, a number confirmed by the EPA. That’s enough water to supply every resident of New Mexico for three months. NMED estimates that the company pumped nearly nine billion gallons from the San Andres-Glorieta between 2000 and 2015 alone.

On multiple occasions, the Pueblo of Acoma challenged the company’s efforts to drill more wells for remediation purposes. According to a letter sent to the EPA by tribal officials in 2021, this action was taken on the grounds that such drilling would threaten “senior water users,” including the tribe. “The United States did nothing,” the letter said. (The U.S. has a federal trust responsibility to tribes that stems from historic treaties.)

All this has taken a toll. While the San Andres-Glorieta aquifer is “highly productive,” an NMED document from 2020 stated, water levels have “dropped significantly through the years,” with Homestake having “played a significant role in mining groundwater” from the aquifer. In some places, water well levels have fallen by 50 feet, and at least one spring has run dry. In a water-strapped state like New Mexico, mining and milling activities, along with the municipal development that arrived with extraction, profoundly depleted the aquifer, according to a 2023 study by the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

Two organizations, Blue Water Valley Downstream Alliance and MASE, first flagged what they saw as Homestake’s overuse of the San Andres-Glorieta at a key NMED permit renewal hearing in 2014. Fast forward to the beginning of 2024, when the company discontinued its use of groundwater from the San Andres-Glorieta. Now, Homestake only relies on treated water from its own reverse-osmosis treatment plant to keep up the hydraulic barrier, according to the EPA.

It’s hard to visualize such an underground fortification — on maps, it looks like a cashew-shaped moat that wraps around the west and south sides of the large tailings pile — or the timescale needed for its maintenance. In 1982, Homestake said it would “require operation for a considerable amount of time.” In response, NMED declared that Homestake had to commit to operating the system until it “can be demonstrated that contaminants in the groundwater will not exceed New Mexico Water Quality Control Commission standards off Homestake’s property in the foreseeable future.”

Advocates believe that means forever. If barrier maintenance is stopped, experts contend that highly contaminated groundwater will migrate southward and downward and eventually make its way to the subcrop, an entry point into the San Andres-Glorieta, municipal supply wells for Milan and Grants and eventually the Río San José. “This signals a bleak future for the stream system and for future generations,” Laura Watchempino warns.

Bluewater’s plume is coming from the northwest; Homestake’s plumes from the northeast. Models show that all are converging, like a Venn diagram, in a location where groundwater flows toward the subcrop. On one side, the hydraulic barrier is warding off some of that pollution, but when it stops operation completely, those contaminants will very likely infiltrate the San Andres-Glorieta, according to NMED.

In the past, it’s been difficult to discern what contaminants belong to what polluter, especially when they mingle, as is the case here. But in 2019, the USGS published the findings of a study that “fingerprinted” such mine and mill contaminants to show their point of origin. According to that study’s author, Johanna Blake, Homestake has a fingerprint that sets it apart from other regional polluters, meaning that it could be possible to more precisely apportion responsibility to the company and apply the same technology to groundwater contamination in the region.

Homestake, for its part, says it has over more than 100 groundwater monitoring wells where the lion’s share of its contamination is concentrated. These show a spectrum of concentrations of uranium — from well below the drinking water standard to extremely high — closest to the unlined tailings piles. By comparison, only three have been installed in the subcrop area. Conspicuously, no water quality samples have been collected or reported there, Maest pointed out in her 2023 memo.

“We’ve been poisoned to the gills,” says Christine Lowery, the Cibola county commissioner. “The question is: How do we recover and live with contamination?”

This story was originally published at Searchlight New Mexico, a NMPBS partner. Searchlight New Mexico is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that seeks to empower New Mexicans to demand honest and effective public policy.