Former U.S. Attorney offers few answers on controversial ATF sting

By Jeff Proctor, New Mexico In Depth

Damon Martinez says he would take “seriously” allegations of racial profiling and other questionable tactics alleged about a four-month federal drug and gun sting operation last year if he were still U.S. Attorney for the District of New Mexico.

But he won’t say how he viewed his responsibilities for the operation while in the job, which he held until March of this year.

He won’t even say whether his former job would have included oversight of the increasingly controversial sting operation despite U.S. Department of Justice manuals describing some of those responsibilities.

“I can’t discuss the facts concerning this case,” Martinez said of the 2016 operation, conducted largely by the federal bureau of Alcohol Tobacco Firearms and Explosives (ATF).

More than half a dozen times during an interview with New Mexico In Depth and New Mexico in Focus, Martinez claimed a host of restrictions that he said barred him from answering most questions — even those involving his opinion — about the operation.

In 39 minutes of questioning, Martinez divulged little about the sting and offered few direct answers.

Watch the full interview here:

The interview came after nearly two months of negotiations with Martinez, the first current or former federal official to agree to sit down for an extensive interview about the operation, which has been the subject of a multipart series by NMID and featured in two NMIF segments.

Officials from ATF and the U.S. Attorney’s Office over the past five months have repeatedly refused requests for interviews and information about the sting.

Martinez was ousted from his job in March by President Donald Trump and is now working for one of the state’s largest law firms, Albuquerque-based Modrall Sperling.

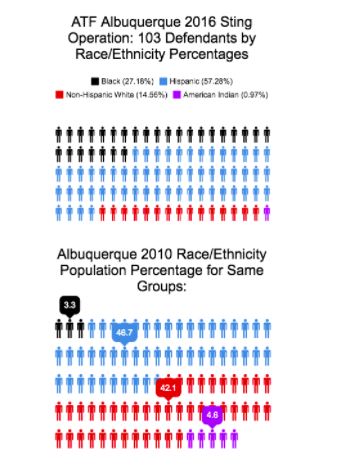

The NMID investigation has found that ATF used paid, professional “confidential informants” who employed questionable tactics to target and arrest 103 people, including a highly disproportionate number of black people. Hispanics were overrepresented among those arrested, too, while whites were grossly underrepresented.

In one case, an ATF informant is alleged to have lured a woman who was trying to recover from heroin addiction at a state-funded halfway house into a sexual relationship, then two drug deals before agents arrested her.

And in most cases, those arrested were not the violent felons trafficking in large quantities of drugs and guns federal officials said they were after, NMID found.

Among the looming questions is how ATF chose Albuquerque as the ninth city where it would conduct an “Enhanced Enforcement Initiative” operation. One of the the agents who led the Albuquerque sting testified in a federal court hearing in April that “individuals with political power” invited the agency to the city to tackle its skyrocketing crime.

Citing “internal communications,” Martinez would not say whether he was involved in the invitation or how he came to learn about the ATF’s enforcement program.

But his successor, Acting U.S. Attorney James Tierney, told black community leaders in a meeting last month that he and Martinez had asked the agency to come to Albuquerque, according to two people who attended the meeting.

Tierney, who served as Martinez’s top deputy in the office before ascending to the top spot this spring, “told us, ‘We initiated it; it didn’t come from Washington,’” Eric Nixon of the Sankofa Men’s Leadership Exchange said in an interview. “He said they brought ATF in because they had done this type of operation before. They shopped for it.”

Tierney would not answer questions for this story.

Martinez hinted at some of what led federal prosecutors on their search for a plan, pointing out that, by the time the ATF operation began, the Albuquerque Police Department was down 100 officers from mid-1990s levels. The city’s population, he said, had grown by 150,000 people.

Against that backdrop, Martinez said, New Mexico had climbed to second highest in the nation for violent crime.

“Albuquerque’s in the middle of a crime wave, and the APD obviously didn’t have the amount of officers it needed to counteract this crime wave,” he said. “And so to the extent that the federal authorities could become part of fighting this crime wave, that was part of the point behind this investigation.”

However, Martinez would not answer questions about his role in planning or designing the operation with ATF in advance. He cited the “deliberative process,” one of several privileges he used during the interview to decline to answer questions.

He also cited the attorney-client privilege, “government ethics” regulations, “non-public information” and the Rules of Professional Conduct in declining to answer questions.

Martinez said he did not seek to waive the privileges in advance of the interview, but that he would “look into” asking DOJ officials for permission to discuss specifics of the operation in a future interview.

Martinez did address why the ATF targeted Albuquerque’s International District, an impoverished, largely minority section of the southeast part of the city.

He pointed to an Albuquerque “Journal article” published last month that cited a Mayor Richard Berry-commissioned report on crime overseen by Scott Darnell, Gov. Susana Martinez’s former spokesman and deputy chief of staff.

“From what has come out in the Journal, it looks like there is a lot of crime in that area,” Martinez said. Darnell’s report was published this August, a year after the ATF operation concluded.

In fact, Darnell used information from 2014 to 2016 to examine five areas of the city. The report found that the area encompassing the International District — several times larger than the other four areas by population and square mileage — had the highest number of violent crime incidents, but the third-highest per capita rate for violent crimes and for the addresses of people accused of committing them.

Martinez would not say what information was shared with ATF agents in advance of the operation, and he would not say why the federal law enforcement agency didn’t target the two areas of town with higher crime concentrations.

During the interview, he reiterated the quantities of guns and drugs seized in the operation: 17 pounds of meth, 2.5 pounds of heroin, 1.5 pounds of cocaine and 127 firearms. He would not say whether he considered the sting a success or whether those arrested met the “worst of the worst” criteria he and other federal officials touted at its conclusion.

Martinez said the U.S. Attorney’s Office adopted a national “worst of the worst” anti-violence initiative in 2011. He “expanded” and “retooled” that program as the crime spike began to grip Albuquerque and after two police officers were killed in the line of duty in 2015.

Martinez would not answer questions about the disparities in criminal histories and ongoing illegal activity by some of those arrested in the “worst of the worst” program — including Davon Lymon , a man accused of killing APD officer Daniel Webster in 2015 — and those arrested in the ATF operation.

NMID has found that many swept up by ATF had no violent felonies in their backgrounds. Some of them were homeless or living in cars and struggling with drug addictions.

Martinez said he took allegations of racial profiling and questionable tactics seriously as a federal prosecutor. Those claims are the subject of litigation playing out in federal court now in a few of the cases stemming from the ATF sting.

“Obviously we’re here because there are concerns,” he added, although he would not answer questions about the racial disparities among those arrested. “I’m really sad about this.”

NMID’s stories have led to a call for congressional investigations of the operation and a rebuke of the ATF from the city of Albuquerque. City Councilor Pat Davis, who is running against Martinez in the Democratic primary for the Albuquerque-based congressional seat, is sponsoring the resolution.

Martinez refused to comment on Davis’ resolution, and he would not say whether he supports a congressional investigation. He also would not say whether he plans to campaign for Congress on the results of the ATF operation, or whether he would have recommended the ATF program to a U.S. Attorney in another jurisdiction.

“To the extent that there are individuals who are prosecuted and who are no longer a threat to the community, that is part of my record, and that is part of how I go forward,” Martinez said. “It was my obligation as the U.S. Attorney during that time period to do what I could to make our city safer, to make our streets safe.

Crime rates have continued to increase in Albuquerque and in the International District since the ATF sting wrapped up. Asked whether the city is safer as a result of the operation, Martinez replied: “I stand on the facts.”

For more of Jeff Proctor’s reporting on this story and our interview with Damon Martinez, click here