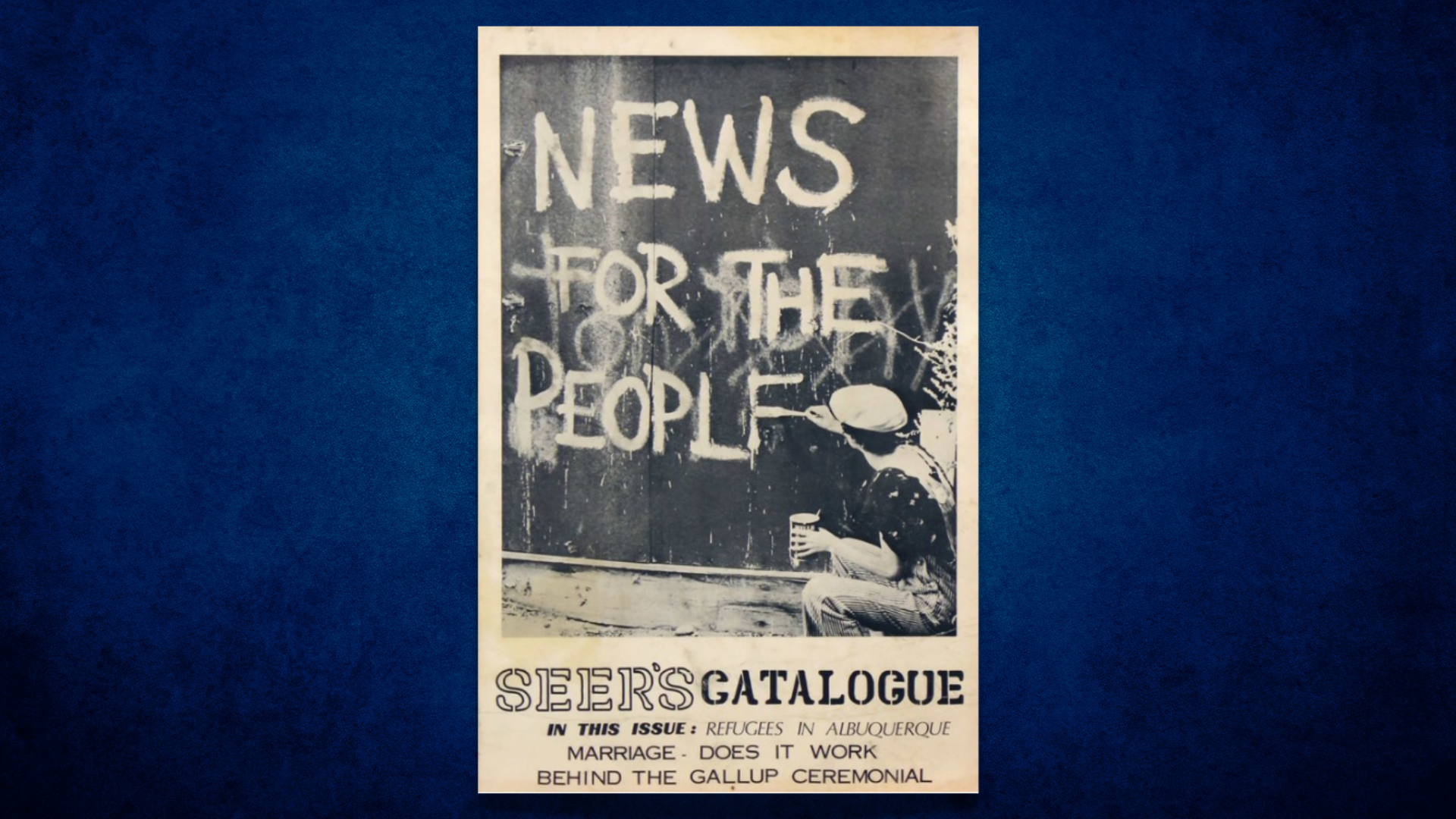

News for the People

I’ve approached this space recently with a clear idea of what I wanted to say: context on the importance of citizen police oversight in Albuquerque, which we tackled in last week’s episode of New Mexico in Focus, and some reflections on why I’m still a journalist the week before that.

Today, such clarity abandoned me, replaced by a socking in of the low-drifting clouds I’ve known too often in my decades at the keyboard. The working headline for what you’re reading now has, for the last 90 minutes, been, “The Tyranny of the Blank Page.”

But in addition to the aforementioned question of why, another conundrum has found its way with increasing frequency to the front of my mind: If I’m to remain a journalist, for whom is the journalism? A lovely field piece that aired in this week’s show — courtesy of NMiF Producer Antonio Sanchez and photojournalist Robert McDermott — offered a new lens through which to interrogate.

“News for the People: Local Journalism in the 1970s” will be on display at the Albuquerque Museum through early March. You really ought to see it if you haven’t already, if even just for the array of what now pass as vintage tools of the craft. As you’ll see when you watch Antonio’s and Bobby’s piece, the exbibit explores the big themes of the era: protest, turmoil and the women’s movement at long last arriving in local newsrooms en masse.

The exhibit’s title, though, is what has my gears grinding: News for the People…

I began my professional career at the Albuquerque Journal at a time when daily newspapers still maintained a squeeze on agenda setting, conversation framing and information distribution. The model was simple: Bundle up as many relevant facts as we could each day and toss them in your driveway overnight.

One might call that spamming nowadays.

The mechanism, in important ways, enabled a philosophy that guided the way we wrote stories at the Journal. This ethos was apparent in national publications, too, and in television news broadcasts. Because of the quasi-monopoly the news media had on information, we were taught that every story was for every person.

News for the people, indeed.

This posture led to criticism that we were, among other sins, dumbing down what we were delivering. Tough, but often fair. Still, I can hear the principle of journalistic populism dripping, gruff and grim, through the Journal city editor’s words every time I had “overwritten” a story.

The idea of big-tent journalism is sprinkled all throughout the Albuquerque Museum’s exhibit: in the headlines, the multimedia pieces and the rest. Presenting stories for everyone, all the time, clearly predated my arrival on the scene in the very early 2000s.

But in 2008, everything changed. The internet, which most news organizations had not taken seriously enough, was democratizing information faster than we could adapt. The Great Recession was upending legacy media’s business model. Social media was elbowing its way into the conversation, promising for free what we’d used to pay our mortgages.

Something else changed, too, mostly on account of necessity. We began to talk about audience in a way we’d not before. (Now, 15 years on, most news organizations have whole teams dedicated to “audience engagement.”) News for the people wasn’t going to change as a guiding light, but which people became an important part of the ongoing discussion. Should every story still be for every person?

One of my favorite people with whom to explore this question is John Fleck, professor of practice in Water Policy and Governance in UNM’s Department of Economics and the Utton Center’s writer in residence. Before any of that fanciness, Fleck spent a couple of decades writing about water, climate change and more at the Journal and in Southern California. He also started what would become an important blog a hundred years ago, back when blogs could be important, and it remains so today.

I asked Fleck once in 2015 or so how I should be thinking about audience. I’d left the Journal a year or two prior, and I didn’t know who I was making journalism for anymore. I’ll never forget what he told me.

“Sometimes a story is for six people — be they legislators or people who live in a neighborhood you’re writing about,” Fleck said. “Sometimes a story is for a family whose loved one was harmed and other families like theirs. And sometimes a story is still for everyone.”

What Fleck meant, of course, was that some stories are meant to land in front of decision makers and, potentially, to influence them. Others should connect with anyone, as a means to inform, educate, enrage or delight — on the rare occasion, all at once.

I think about that every time I make or help to make a piece of journalism. And I hope that comes through when you watch New Mexico in Focus: Sometimes, you might be one of the six; other times, you’re in the boat with everyone else.

-Jeff Proctor, Executive Producer

-

News for the People

I’ve approached this space recently with a clear idea of what I wanted to say: context on the importance of citizen…

-

30th Anniversary of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial

11.10.23 – We mark this weekend’s Veteran’s Day with a special segment on the dedication of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial in…

-

NM’s Healthcare Workforce Shortage

11.10.23 – New Mexico is grappling with a shortage of medical professionals, especially nurses. Recent reporting from New Mexico In Depth’s…

-

Analyzing Santa Fe’s 2023 Election Results

11.10.23 – This week on New Mexico in Focus, Executive Producer Jeff Proctor chats with Santa Fe Reporter Editor and Publisher…