Pentagon IDs Four More NM Sites at Risk of PFAS Contamination

The Pentagon has identified four more military sites in New Mexico that could be contaminating local waters with PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

On Friday, March 13, just as federal and state agencies ramped up emergency efforts to address the spread of COVID-19, the U.S. Department of Defense released a report summarizing its progress on PFAS issues through the end of last September.

According to its updated list, the military will assess whether activities at the Army National Guard armories in Rio Rancho and Roswell, the Army Aviation Support Facility in Santa Fe, and White Sands Missile Range have polluted groundwater with PFAS. The toxic compounds do not biodegrade, and have been linked to cancer and many other health problems.

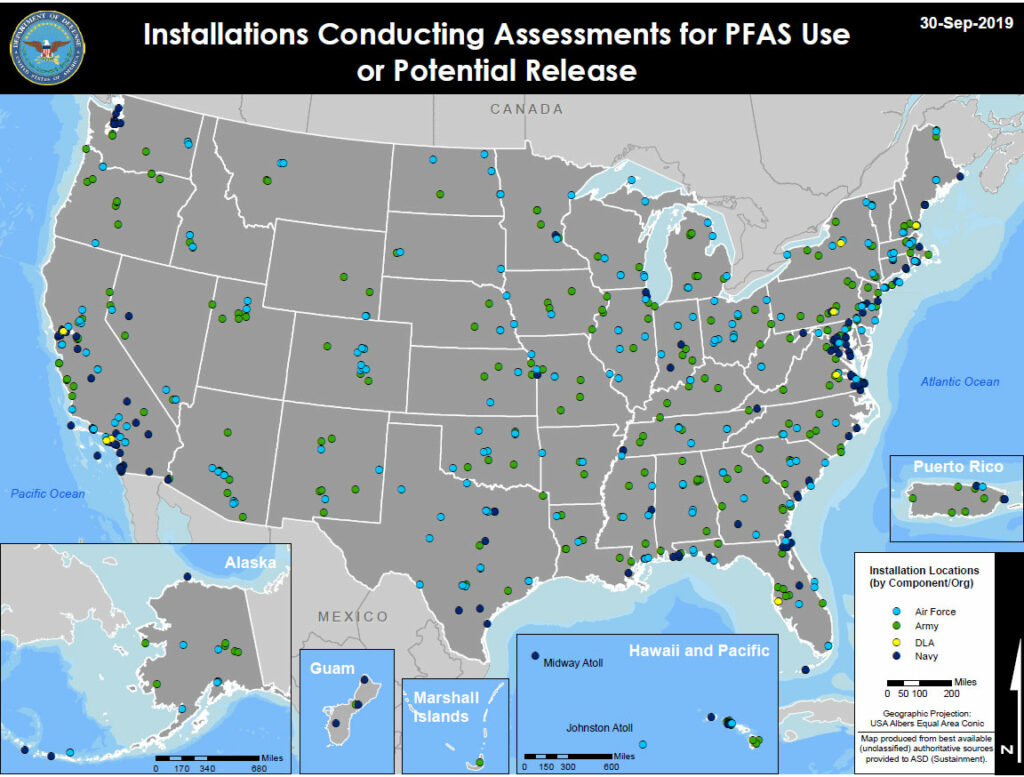

Nationwide, the updated list of military sites under investigation swelled from 450 military locations to 651. The military does not appear to have notified states, including New Mexico, prior to making the list public.

According to the report from the Defense Department’s PFAS Task Force, the military’s earlier investigations focused on contamination from aqueous film forming foams, which the military used for firefighting and training from the 1970s until just a few years ago.

The updated progress report notes that the task force’s expanded investigations now also focus on “installations where PFAS may have been used or released.”

The report does not include details about specific activities that might have exposed people or the environment to PFAS. Defense Department spokesman Chuck Pritchard could not be reached for additional information before publication.

PFAS are a class of thousands of toxic, human-made chemicals that have been linked to reproductive and developmental problems, liver and kidney disease, and immune system problems. Exposure to PFAS has also been tied to high cholesterol, low infant birth weights, thyroid hormone disruption, and cancer, including non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and kidney, testicular, prostate, and ovarian cancers.

Chemicals within the PFAS family are found not only in firefighting foams, but in common household items, like weather-proof clothing, stain-resistant carpet, and nonstick cookware. The chemicals can cross the placental barrier and be passed from mother to child during breastfeeding. They also bioaccumulate, moving up the food chain.

Already, New Mexico is grappling with groundwater contamination from two Air Force bases in the state.

In 2018, the Air Force notified the New Mexico Environment Department that monitoring wells at Cannon Air Force Base had PFAS concentrations more than 370 times what federal regulators consider safe for a lifetime of exposure. The toxic chemicals also tainted nearby private drinking wells. Air Force testing also revealed levels of PFAS up to 1,294,000 parts per trillion—more than 27,000 times the lifetime advisory level—in waters below Holloman Air Force Base near Alamogordo.

In 2017, the Air Force released its site inspection for Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, which concluded that PFAS were either not detected or were present in levels below the EPA’s lifetime health advisory.

Earlier this year, the water utility EPCOR, which serves water to customers in Clovis, revealed that it had detected PFAS in some of its drinking water wells. Some of those tests showed results as early as last summer. The company, which has been voluntarily testing its wells in the absence of a governing federal regulation, says the delay in reporting the contamination was due to the time involved in testing and retesting affected wells and pumping stations.

Since the New Mexico Environment Department issued notices of violation to the Air Force over contamination from the two bases, the state and the military have been locked in litigation over the state’s authority to compel the Air Force to clean up the groundwater contamination.

The new list came as a surprise to state officials.

“To our knowledge, the DOD did not reach out beforehand to inform us that they are expanding their scope to include facilities that had a lesser likelihood of having used PFAS,” said NMED spokeswoman Maddy Hayden. “They also have not informed NMED of when these site inspection reports will be completed or provided.”

Hayden added, “Addressing PFAS contamination in New Mexico communities remains a top priority of the New Mexico Environment Department.”

The recent Defense Department report also notes that the funding for PFAS cleanup included as part of the newly-passed National Defense Authorization Act is inadequate.

According to the report, aircraft rescue and firefighting vehicles will need to be retrofitted entirely—meaning that each vehicle component that came into contact with the firefighting foams will need to be replaced—at a cost of almost $200,000 per vehicle. That alone, according to the report, adds $600 million to earlier cleanup estimates.

Alternately, replacing the Defense Department’s current fleet of about 3,000 contaminated vehicles will cost $4 to $6 billion—and take 18 years. The report also notes that as part of the Defense Authorization Act, the Defense Department has committed $30 million to study PFAS exposure in eight communities near former and current military installations. Those studies are happening in West Virginia, Colorado, Alaska, Massachusetts, Texas, New York, Washington, and Delaware. The military is also “developing a framework” to annually test the blood of military firefighters for PFAS levels.