Rio Grande Already Drying Out Near Socorro

by Laura Paskus

In springtime, rivers are supposed to swell with snowmelt, filling their channels and triggering fish to spawn. This year, however, the Middle Rio Grande has already dried south of Socorro.

Record-low snowpack in the mountains upstream means that the state’s largest river is in trouble this year. And so are the species and communities that depend on it.

Earlier this week, biologists headed to Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge to start scooping up endangered fish from pools and puddles and relocating them to a stretch of the river that is still flowing.

Speaking to NM Political Report Wednesday night, fish biologist Thomas Archdeacon said the salvage crew already collected about 15,000 silvery minnows within the roughly six miles of dry river on the refuge. Those numbers will start dropping quickly.

Since 1996, the Middle Rio Grande has often dried during the summer, sometimes for stretches of 30, 50 or even 90 miles. But drying in early April is nearly unprecedented in the river’s recorded history.

“We had such a great year last year in the river, and the fish are just going to get whacked this year,” said Archdeacon, who works for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the agency mandated to enforce the Endangered Species Act. “It’s especially bad this year because the drying is happening before they spawn,” he said. “Some will probably still spawn, but there’s not enough water to create the habitat that the larval fish need.”

Historically one of the river’s most abundant species, the two-inch long silvery minnow lived throughout the Rio Grande and its tributary, the Pecos. By the 1990s, the fish survived only within a 174-mile stretch of the Rio Grande near Albuquerque, and in 1994, was protected under the Endangered Species Act.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation operates the dams and diversions along the river, and delivers water used by cities and farmers. Officials are watching the situation closely.

“The results of this very dry winter are visible up and down the Rio Grande,” said Reclamation’s spokeswoman Mary Carlson, who added that the agency is working with its partners, such as Fish and Wildlife, the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District and Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority.

Carlson said the agencies are working on a plan to create a pulse of water to help the fish spawn. Later this month, biologists are already scheduled to collect eggs; those they find will be raised in hatcheries.

“Reclamation currently has 11,600 acre-feet of water in storage to supplement the Rio Grande flows,” she said. “With a snowpack that is among the worst on record, we must weigh our options and manage this water in a way where it will provide the most benefit to the Rio Grande ecosystem.”

The Rio Grande’s early drying is just the latest signal that the state’s water problems demand close attention, particularly as the region continues to warm.

Thanks to warm, dry conditions and a lack of snowpack, experts are worried about fire season in New Mexico, which began months earlier than in the past. This week, the U.S. Department of Agriculture also designated 12 counties in New Mexico as primary natural disaster areas due to losses and damages caused by drought. Farmers and ranchers in 15 other counties also qualify for natural disaster assistance programs and loans.

That means all but six of the state’s 33 counties are affected by drought—before planting season has even begun in most areas.

Meanwhile, New Mexico is embroiled in a lawsuit on the Rio Grande over water rights.

In 2013, Texas sued New Mexico and Colorado, alleging that by allowing farmers in southern New Mexico to pump from groundwater wells near the Rio Grande, the state has failed—for decades—to send its legal share of water downstream. In a unanimous opinion last month, the U.S. Supreme Court also allowed the federal government to pursue its claims that New Mexico has harmed its ability to deliver water under the Rio Grande Compact and its international treaty with Mexico.

Were New Mexico to lose against Texas and the federal government, the state could be forced to curtail groundwater pumping and pay damages of a billion dollars or more.

This isn’t the first year Archdeacon has been out in the river channel, seining puddles for the endangered minnows—while having to leave behind carp, red shiners and other fish. Usually, they’re out there in late June or July, before monsoon rains give the river a boost.

This is the earliest his crews have ever done salvage work.

He realizes some people might not care about the survival of the silvery minnow itself. But he says it’s worth remembering that the minnow is an “umbrella species” for the Rio Grande.

“Maybe the minnow’s not that important, but if it weren’t there, it would be dry every year, and we wouldn’t have any of this—it would be like the Salt River in Phoenix,” he said. The Salt River is just one of the southwestern rivers that has dried entirely due to overuse. “By being a protected species, it’s protecting everything else that’s around in the bosque.”

This story originally appeared on New Mexico Political Report

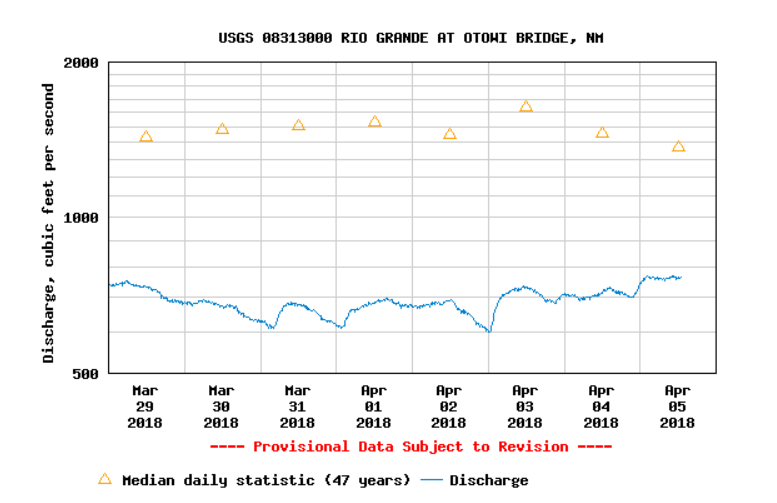

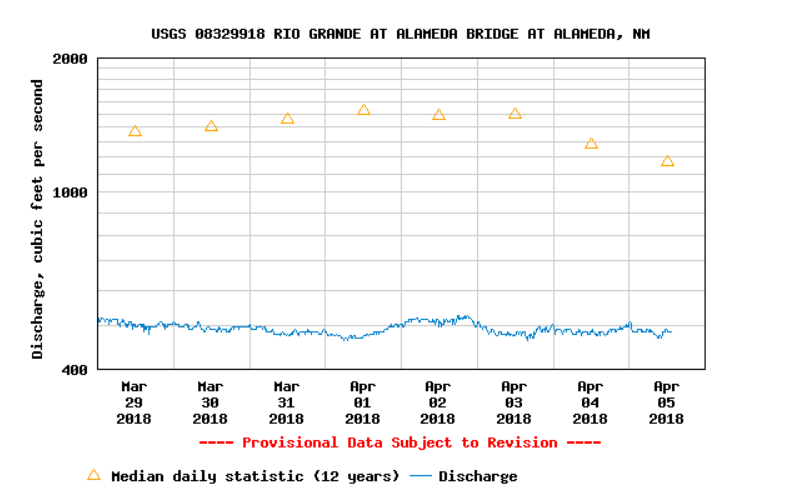

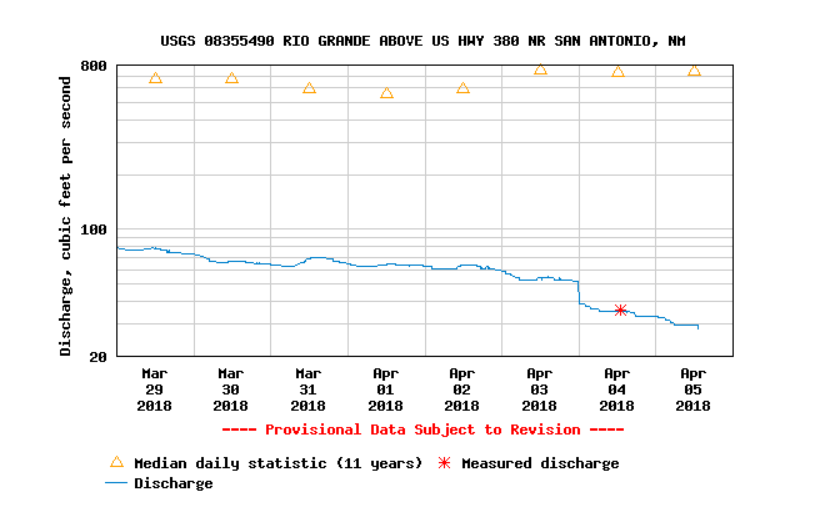

The USGS streamflow gages are available to view online, and include current conditions as well as median daily statistics. We’ve included below information from April 5, 2018 for three stream gages: Otowi, just south of the Colorado border; Alameda Bridge north of Albuquerque; and above the Highway 380 bridge in San Antonio, N.M.

[…] day long.” Now, water diversions, development and climate change leave more sections of the river dry each year. “If you jump, you’re just going to hit the dirt,” said Bazan. Nobody has bothered […]

[…] Now, water diversions, development and climate change leave more sections of the river dry each year. “If you jump, you’re just going to hit the dirt,” said Bazan. Nobody has […]