New Mexico & the Vietnam War: Portrait of a Generation

TOM BACA

Through The Lens

Photos of and by Don Loftis

Most of these photographs were taken with a Kodak camera given to Don as a gift from his grandmother. The camera stopped working when monsoon season began.

Tom's Story

(Note: this is the full transcript of the Baca interview, edited only for readability)

About 1957, I was at Albuquerque’s Our Lady of Fatima Elementary school and I saw my first helicopter. And, I started dreaming about helicopters. There was a television program called ‘Whirlybirds’ in the late 50s and Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz produced this series. I just got hooked on these helicopters. I would go out to the airport and wait for a helicopter to land, which was very rare here in Albuquerque back in the 50s. And sometimes army helicopters would come in, and I would just glue myself to those guys.

In high school at St. Pius, I got my first ride in a helicopter. And I was sold. I said "I am going to go into the Army, and I'm going to be a helicopter pilot. This is when I'm about 15 years old. I graduated from high school in 1963. I was a really good "D" student. And I had to have permission to join the Army, my parents had to sign paperwork. I went ahead and joined the army on June 14th, Flag Day of 1963, and went to Ft. Polk, Louisiana for basic training.

The Baca family's military history dates way back to the 1600s and so, maybe 1700s, and I'm very proud that they helped settle this land. My ancestors came up the King's Highway, Camino Real and I have names and dates in a very detailed family biography. You can go back each generation and every generation had a mention of military service. I'm absolutely proud of the lineage of the Baca family. I mean, when you read what they accomplished and back hundreds of years ago, how difficult it was to just live. To just find food. To find shelter. We really don't have a clue in our generation how hard it was on those folks. And, the extreme conditions they had to work with. The illnesses, the weather, the starvation, the wars.

"The army was, to me, a way to get what I wanted. And, after I got in, I loved it."

The army was, to me, a way to get what I wanted. And, after I got in, I loved it. But am I proud of the lineage I learned about? Yes. Absolutely. I have an uncle, for instance, he's still alive. He's 93 and he was a waist gunner on a B-24 in the Second World War. I have so much respect for my uncle, what he went through.

I didn't really go in the army to go in the army. I went in the army to learn how to fly helicopters, and was that selfish? Well, something has to motivate you to do something. But, once I got in the army, I loved it. I loved what it stood for. I love what it did for me. What it did for my wife and my children. And, what it did for the American people during my tenure in the army. I'm just very proud of all of it.

I was scared because the first six weeks of the primary helicopter school warrant officer flight training curriculum was harassment and let's see if we can chase this guy out of here. I remember my instructor was a civilian. His name was Arnold Mackie, and he had a knife, and if I didn't fly the helicopter right, if I was over controlling on the cycling stick, he would stab me in the hand. And I still have a scar today to show that. But Arnold Mackie was a very patient man, and he finally said "well I guess I can let you go out and kill yourself." And so he got out of the helicopter and he says "oh, one thing I haven't told you is this thing is going to fly a whole lot different with me not in it. It's going to pick up differently." And I say "oh thanks for telling me that." I did it, and I took it off, and I got it around the pattern three times and landed. And on the way back to the barracks that night on the bus, we stopped at the Holiday Inn because everybody that soloed got thrown into the swimming pool at the Holiday Inn in Mineral Wells, Texas. Of course, I didn't tell them I couldn't swim, but I managed not to drown.

My first solo flight I was just concentrating on not making any mistakes, not doing anything stupid, not exceeding the limitations of the aircraft. RPM. My control touch and control of the aircraft was reasonably good, for a guy with 17 hours of flight time. But, you know, you're there by yourself. What it you have the engine failure? We practiced that many times. They got us professional enough where if something happened on our first solo, we could probably get it on the ground and live. You're just so happy that they thought you were good enough to fly that thing solo. It was great. It was just superb. And, I came down and I landed that thing. And I shut it down, got the rotors stopped and I was, just, I was almost in tears I was so happy, because I knew that I was going to meet my goal.

I remember I was really excited about going to Vietnam. I got to Travis Air Force Base, and I was to go over to Vietnam on a C1-41, the new heavy lifter the Air Force had. Well, being a pilot, they have one window on a fuselage of that thing, and I managed to get it. So I was able to film our approach into the Nha Trane area of Vietnam from that window. And that was my first view. I was assigned to the first Cav division and we went to Bien Hoa Air Force Base. I think I had two days of rest from the trip, and I started flying. My biggest problem was being able to find my way around South Vietnam, because there were not a lot of navigation aids and we didn't have much in the aircraft. We had a map on our lap. Six weeks after I got there, I was made aircraft commander and that surprised me because I knew guys who I thought were better pilots than I that weren't aircraft commander. We did combat assaults in our helicopters and we flew US and Vietnamese army troops into LZs. Some of them with firefights going on as we were landing. My first year in Vietnam, I got almost 1200 hours of flight time.

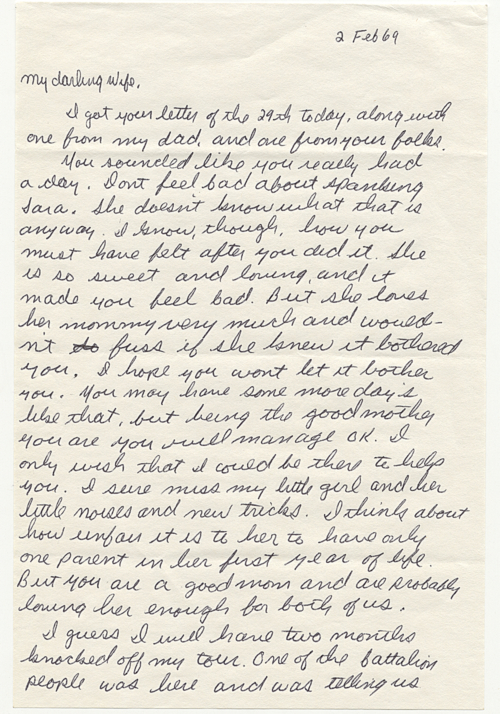

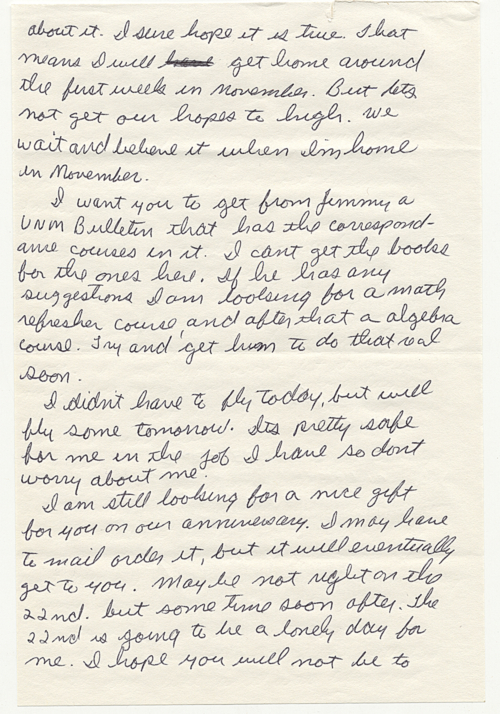

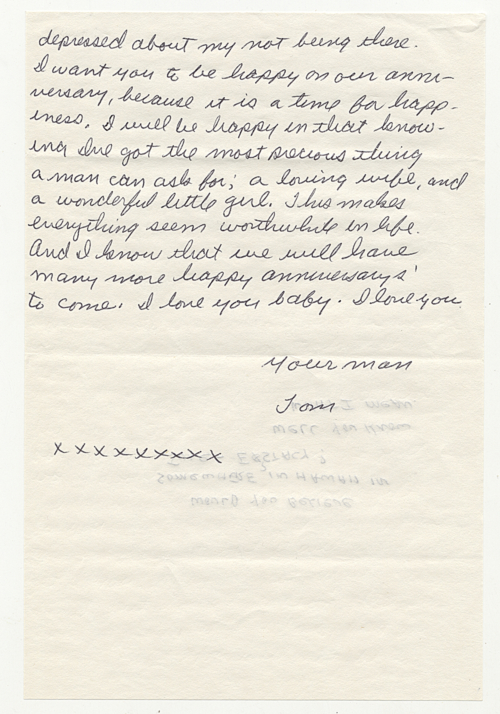

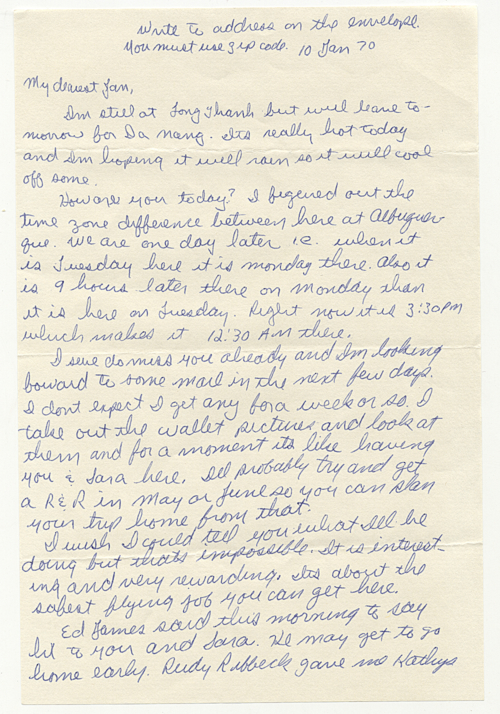

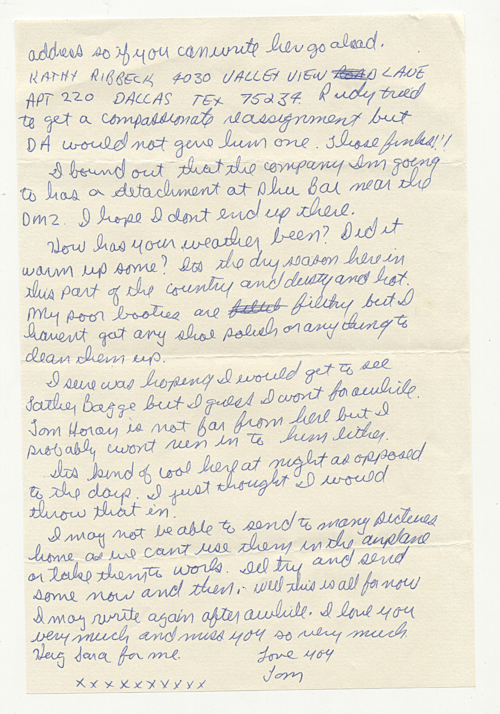

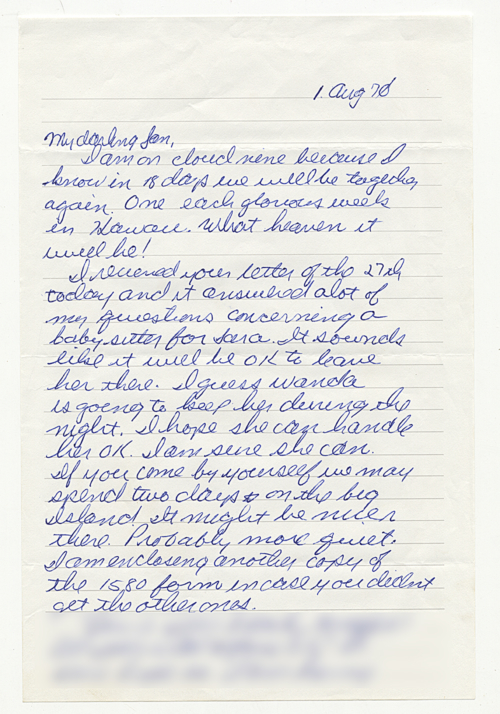

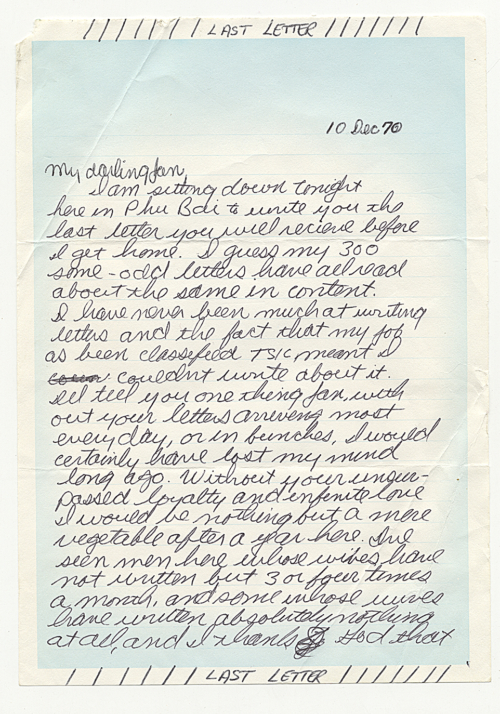

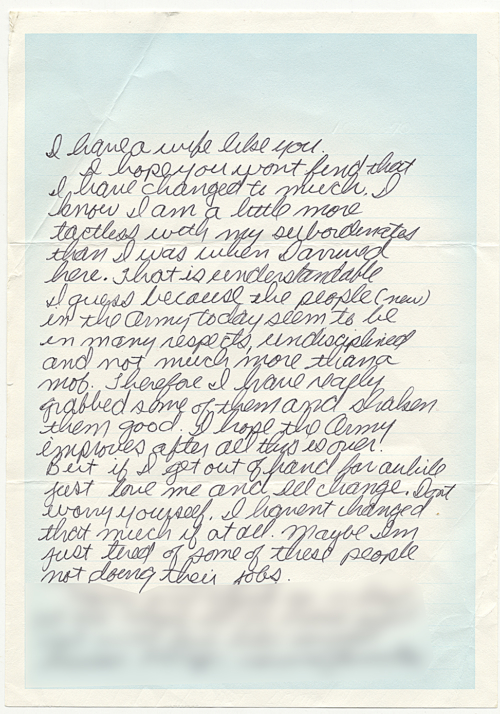

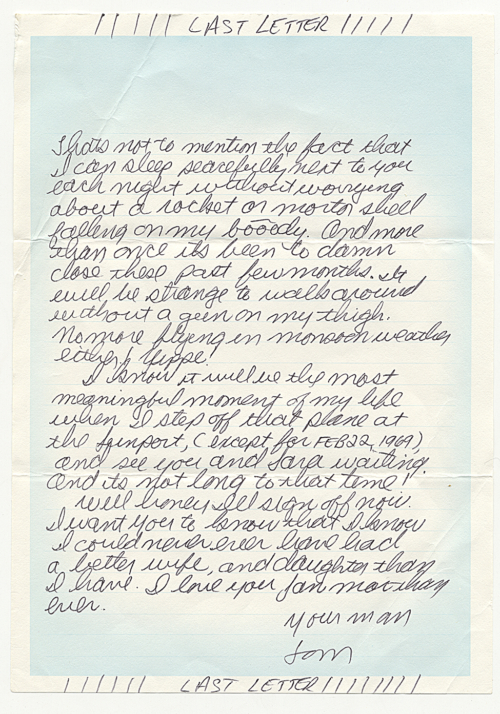

As a young warrant officer, my first year in Vietnam, I was very patriotic. I thought that if the United States was doing this, it must be good. So yeah, I was patriotic, and I thought it was a good thing we were doing it. But my second year was totally different. I could write my wife letters, and she saved them all, they're sitting in the cabinet right behind me. And some of those letters are pretty depressing about what I thought and what I saw my second year there in Vietnam. And what I was reading about what was going on in the United States about the war. And I came to the conclusion that we need to get out of here and let these people settle this among themselves.

There was so much compassion shown by everybody over there that I was associated with. Yeah, there were some war crimes. There were the Calley things that went on, but for the most part, if we saw an injured North Vietnamese soldier or Viet Cong, we were compassionate to them. We helped them medically. We medevaced them. We weren't just cold-blooded killers there to do that. None of the people I served with there were like that. There were some people over there, but I never had to be around them.

One of the saddest things, I had a very good friend in flight school. He and I were the same age. He was from Pennsylvania. His name was Davey Coons. And we were both warrant officers. And I've got video and pictures of him, and his was one of the freakish deaths in Vietnam. He was just flying 500 feet above the ground. One bullet comes up, hits him in the neck, and he bleeds out that quick. It got his vital arteries, the jugular and everything. That was September 19th, 1966. And I remember going in for dinner. We lived in a Villa and we had good living conditions. And Tommy Thornton, my platoon commander, came out and he says, "I need to talk to you." He says, "Davey Coons was killed today." And that hit me harder than any of the other people that were killed I knew, for some reason, on both tours. And I think it was because he and I were the same age, and we both came into the Army for the same thing, and we got along, and we were just good friends. And then another roommate of mine, Edgar Saffel. He was killed on an assault helicopter. Tail rotor came off. Just fell off. 20 years old. It only happens to them. I guess I probably said "boy, oh boy. That could be me." But, I just never dwelt on it. I never thought about it. Just went out and flew my missions. Did the best I could do.

My first combat mission was kind of scary. The gun ships were strafing the barriers of the LZ. I think it was July 24, I got shot down the first time. It was about a week, or a week and a half, before they made me aircraft commander. And I was flying with the captain, and we went into an LZ, and we started taking numerous hits on the aircraft. One of the South Vietnamese troops was killed where he was sitting. The rounds took out our engine, oil pressure, our transmission oil pressure, and our hydraulics. And we landed in the LZ. And the people behind us thought we were going to explode. They said “Get out of there. Get out of there.” I knew the aircraft would fly for a little bit without lubrication. It's really hard to fly a Huey without hydraulics; it's like losing the power steering on your car, except you need very minute movements on these controls to do what you want the aircraft to do. So we flew maybe 2000 meters out of the LZ, and then we had to land. We landed into this swamp area. We got out the aircraft. We had two wounded and one dead on the aircraft, and we sank into the mud, up to our knees, we could hardly move. But we got the radios out, we got the machine guns out, we got the wounded out, and some other Huey’s came in and picked us up.

I was thinking about should we get out of this aircraft right here in this hot LZ, or should we try to fly it out of here? And Captain Horn and I looked at each other, and things weren't looking good outside of the aircraft, and we decided to fly it out. I kept thinking, jeez, why did they shoot at the back of the aircraft where the troops were, instead of where the pilots were? And I had that thought more than once in Vietnam. Why didn't they shoot the pilots that would take the whole aircraft down? So I was thinking, and I knew we had wounded on board, and I was thinking well we need to get them out of here. We need to get away from this. And I wasn't necessarily scared, I was just trying to figure out what's the best thing to do. I don't think I ever got shaking scared in Vietnam. I didn't, you know, because when you're young, nothing can happen to you. It happens to the other guys. A lot of vets say that; it's kind of a cliché, but it's true. That's what you think when you're 19 years old or 20 years old, and you're over there doing that stuff. That's not going to happen to me. So I never really got scared. I was concerned a couple of times, but not scared. At any rate, we got back, and everything turned out okay. There were several other incidents that first year. I lost a tail rotor going into a landing zone on a combat assault in the middle of the formation. I ended up landing with a formation, and how the heck we managed to do that when the tail rotor was shot off basically is what happened. And I had two more hydraulic failures.

A memorable event happened on May 17th of 1967. I had transferred from the assault helicopter company to the second field force headquarters to fly the generals. They needed a pilot that knew his way around Three Corps. They needed a pilot that had proven himself. Twelve days before I was to leave to come back to Vietnam, I was flying the Second Field Force Staff Chaplain to a Special Forces camp. As I landed there to let the chaplain off, a captain who was the A-Team commander came running out of the bunker saying "we've got a bad situation, can you do some med-evacs?." And I had the General's ship, you know, shiny, brand new Huey, you know, just beautiful, and I said ‘sure, where is it?’

Wally Johnson was the captain. Well I took him and a medic into what could be considered a really bad landing zone. It had bamboo about twenty feet high, which is higher than a rotor disk on a Huey, and it was along a trail, and you couldn't really see down through the bamboo. You could see this little cut, where this trail was and where all these people were, and there was about a 120 of them. And, they had a lot of casualties. I think they loaded up eight wounded. These were South Vietnamese army troops. And Wally Johnson said get back to the camp, get these wounded into the medic area and then come back and get me. Well I landed at Cau Song Bay, and a lieutenant came out and he says "Can you get some other aircraft to help? We've got to get them all out of there." And so, believe it or not, I did a call for any helicopter in that area to give me a call. And it's a guy named Jack Swickert, and Jack was from Albuquerque. He had been a reporter at the Tribune, and Jack knew my twin brother Jim before he knew me. He didn't even know that I had a twin. He didn't know my twin had a twin. He was with the 118th Assault helicopter company, so he joined me, and we had two ships. He had machine guns on his. I had none because it was a VIP Huey, and we just didn't have machine guns on it that day. We were asked to extract all of the remaining troops, and we figured between the two of us, it was going to take at least five trips to get the hundred or so out of there. The problem was that the battle was still going on, and they were still getting casualties. They were still getting KIAs, and so the battle was moving, so we didn't know exactly where to land in this bamboo forest. We could only see the trail, and each time we landed, we were tearing up the rotor blades. My main concern was the tail rotor, if we lost that, if would have been bad. As we were landing and loading people up, I was really wondering why they weren't shooting the pilots. Come to find out later, intelligence said that after we got everybody back, that these were North Vietnamese troops and there was about 700 of them. They were trying to make it back to Cambodia after this operation Junction City, which was the largest operation of the Vietnam War.

Well the first trip in that I did with Captain Johnson, I looked at the bamboo and stuff and I looked at the blades, and I said if I can keep that tail rotor in the middle of that trail, and if I don't turn the aircraft more than ten or fifteen degrees as I'm getting down into that trail, I'm going to try it. I'm going to see if those blades hack off that bamboo like a lawn mower. And boy it did, but it was noisy, and it was scary. It looked like a power mower on your grass. There was just stuff flying everywhere, and I started getting concerned about debris hitting the tail rotor or the engine vents getting clogged up with bamboo, because then we'd have compressor stalled engine failure. But I said, if I can do this once, I can come back and land in the same spot, it didn't work. We got in. I got back to Cau Song Be as I told you. Jack Wicker joined us, and I looked up at those blades spinning, and I said I really need to take a look at those and I didn't. Like I said in a different film one time, I didn't have time. But it was still flying. The aircraft was still flying, the crew chiefs got out while we were still on the ground, while the aircraft was running. They start pulling the stuff out of the air vents. But we went in five more times and each time we had to cut through the bamboo because we were following the battle, the wounded, and stuff like that. So, you know, it was a calculated risk, I mean, I knew it. It could have been a whole lot worse than it was if the blades hadn’t held up. They were torn up pretty good, but that just goes back to that Huey. It was just a great, great flying machine. It could take a real beating, and I was so happy to be flying that thing.

I'm thinking, 'Jesus, I've only got twelve day left in Vietnam, why am I doing this now?' I could have refused the mission, but that just wasn't me. I had a new pilot with me, Captain Larry Liss and we just said 'we're going to do this.' You know, we got to do it. But as I'm landing in there the first time, with Captain Johnson, I'm going 'this is either going to be really good or it's going to be a disaster.' And when I took off out of there, and he had asked me to come back and pick him up, I was really concerned about that I got away with it once, what about twice? I said, well, I'll land in the same spot, and it didn't work. The battle was moving, and so I figured if I got in there once, if I get down a second time though that bamboo with Jack, and the thing will take off again. I know I'm okay, you know, because the blades are holding together, and so each time we landed we had that going through our minds. And, back in 2008, I went back to the site of that mission, and looked at the bamboo and I said 'I can't believe we did that five times and got out of there without destroying the aircraft.' The big thing was that the last time out of that LZ, I had 18 people on the aircraft because we couldn't leave five or six there; they would have been taken out. So we overloaded the aircraft, fortunately we were getting pretty low on fuel, so that weight was going away. By the way, that day, May 17, ‘67, I got more flight time that day, in one day than any other day on either tour in Vietnam. I got 10.7 hours of flight time that day, in a helicopter. That's a lot of flight time.

The battle's going on around me. Why didn't they shoot the pilots? They're shooting the people getting on the aircraft, okay? And on Jack's aircraft, they shot two or three people as they were getting into the Huey. The only reason why I could think that they didn't kill us, the pilots, was that they wanted us out there so they could continue their journey to Cambodia.

I know I damaged the belly of the aircraft by landing on a really thick, sharp piece of bamboo, and I didn't know that. It punched a hole in the belly of the aircraft. The thing about that is that's where the fuel cell is, and we didn't realize that, even the night we got back to Bien Hoa. We didn't know that until the next day, when they brought me out, and asked me to explain what happened to the General's helicopter. They said, ‘did you see the whole on the bottom of the aircraft?’ And I said 'no, I didn't know we had a hole.' And they said, 'yeah, take a look at it.' And we had crash worthy fuel cells by then, but that thing had poked about half way through that fuel cell. If that had penetrated that, it would have been all over.

You could hear rifles firing. You could hear machine guns. You could hear people yelling, even though the helicopter was running and you had a helmet on. I mean, there was an amazing amount of noise, for such a confined area. The battle was taking place, like 50 meters from us.

The shooting was going on from the right side of the aircraft. Which is where Larry was sitting. He took out his AR-15 at one point in the mission and was shooting it out of the aircraft as we took off. That first time, I just said, 'Well, we made it, the General is going to be pissed off about his aircraft.' Then I get back to the camp, and we have to do it at least five more times. And we're going Christ you know. We called for air support, they could not support us because the battle was too close to the friendlies and to us. They couldn’t bomb. They couldn't strafe. They couldn't do anything. So we were kind of on our own. And people ask me ''Why didn't more helicopters come?' Well Operation Junction City had just stopped, and all of the helicopters had pretty much gone back to their bases and were in maintenance.

Each time we landed, additional wounded were getting on board. Some of the people were shot as they were getting on board. Some were killed. We would take the dead ones out; we needed the room for the ones that were still alive. They would jump on the aircraft, and as soon as we saw a load we could take, we'd take off.

Typically, the South Vietnamese were a little smaller than the Americans, and they didn't carry near as much combat gear - backpacks, you know all that stuff that the Americans carried. They all had M1 carbines. So I could maybe put about 12 to 14 on each time. And Jack was doing the same. He may have had a few less because he had the machine guns and ammunition and stuff; and he had an older aircraft. But each time we went out of there we were over gross max weight limitations. And we knew it. Because of the vertical take-off requirement, it was pretty difficult to get out of there. The last trip, I was able to do what they call a running takeoff. That's when I had 18 on board, because we had kind of gone to the western side of this bamboo forest as it was moving, and so I had a little clear path. If I could do a running takeoff, you could get more weight off.

I have no idea why it turned out the way it did; I have no clue why I was not shot, and why the aircraft was not disabled. They could have done it. They absolutely could have done it. Same thing with Jack. To this day, we just go 'huh, how did this happen?'

That was a heck of a day. But it wasn't my scariest time in Vietnam. I had been flying on a very simple, little mission to take some chainsaws, this was still when I was in the assault helicopter company, to a place called Phuoc Vinh. I think the 173rd was there and it was a night flight. And none of liked flying at night in Vietnam in helicopters. We had tried a couple of night assaults that were just almost disastrous. But anyway, I was flying over the river just over Bien Hoa Air Base, and I took a round in the belly of the aircraft. It came up through an igloo water jug that sat right there and hit me in the face, and dropped into my lap. And I had a little nick there, with a little blood. And I said, 'damn, what happened?'

Well we got to Phuoc Vinh, checked out the aircraft, it had a hole in the bottom. We had a hole in the floor. We had an entry and an exit in the igloo water jug, and I had a round in my hand. But the aircraft was fine. It was still flying. We checked it over and said, let's go on back to Bien Hoa and have maintenance check it out. So we dropped our chainsaws, and went back. And I said, oh yeah, it's fine. They patched up the belly of the aircraft. Several nights later, I'm on another night mission to a place about fifteen miles from Bien Hoa Air Bases, just across the river to a place called Phu Loi. I take off and all the sudden I start smelling fuel. We're in the same aircraft that got shot through the floor. I'm smelling fuel, and the crew chief is all “do you smell that fuel?” And I look down, and the chin bowl, just forward of the rudder pedals, and it's filling up with jet fuel. And right there are all the avionics. All the radios. All the electrical connections. The main battery for starting the aircraft. And you know, the helicopter flies kind of nose down. All this fuel is rushing into the front end of the aircraft, and I'm going ‘we're going to die. This thing is going to explode, it's all over.' So I reach up and I turn off all of the electrical stuff, and I land it on a sandbar on this river, and we just ran away from it. What happened, was that round that came up through the floor and igloo water jug and hit me in the face, had nicked the fuel cell. And it finally split open and the fuel just started rushing out.That scared me pretty bad because I didn't want the damn thing to explode. I unfortunately saw some guys that died in fire, and I didn't want to go that way.

About the time Saigon fell, I had returned to the U.S. from my second year in Vietnam. I think the best thing that I saw in Vietnam, and I include both of my tours, is the resilience of the American soldier. The ability to get up every morning and go out and do whatever you had to do, whether you were a cook, an infantryman, a pilot and to go out there and see really horrible things happen, and be able to go out there again. I think the bravery, and the courage, and compassion that the American soldiers, airman, marines, navy, all of them, air force, showed on a daily basis is what really impressed me about the American society and culture. In Vietnam, I just have to say the American soldier and his commitment to do his job is one of the most impressive things I'll ever see. And, they do it in an unselfish manner.

Well my service in Vietnam was satisfying to me personally. I came away with good feelings about what I accomplished there. What other people think about it, I have no clue because most people I run into today, will say, "Thank you for your service." when they find out that you're a veteran. Was it worthwhile? Was the whole war worthwhile? I don't have high enough a pay grade to tell you. I'm just a wage earner. I'm a retired army officer, who continued flying. I'm very proud of my service, my twenty years, not just Vietnam, my whole twenty years. I'm very proud of the people I served with, and I'm glad to have been a part of it. Was it a just war? I don't know. I could tell you, going back to Vietnam today, it turned out really good for them. Whatever happened over there, the bits of capitalism they embraced, in that country today, it is one of the most magnificent places. Modern. Peaceful. I don't think I've felt as safe, walking around a place, and city like Saigon. Nobody has guns, there aren't police all over the place. Everybody is just happy. I'm sure they have crime. But no, my time in the service was good. I'd do it exactly the same. I wouldn't change one single thing.

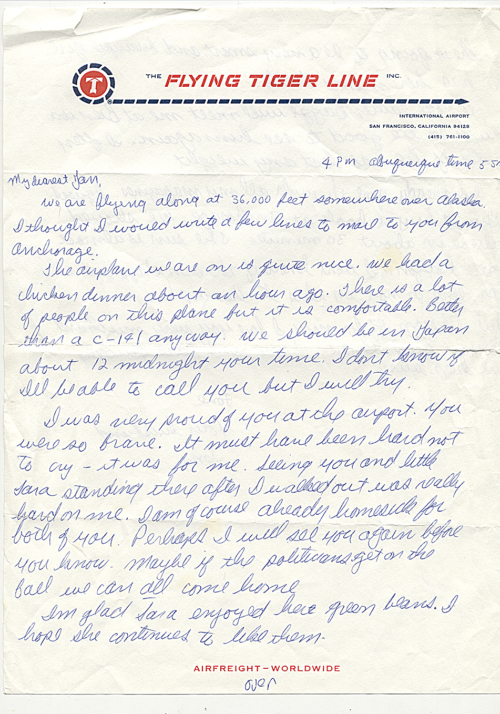

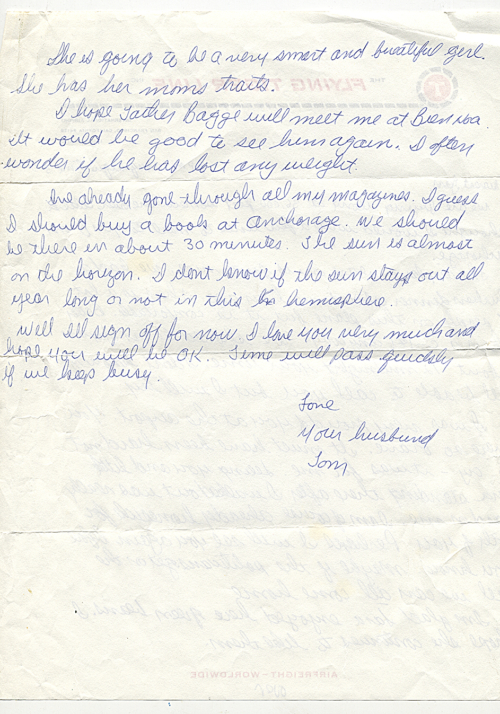

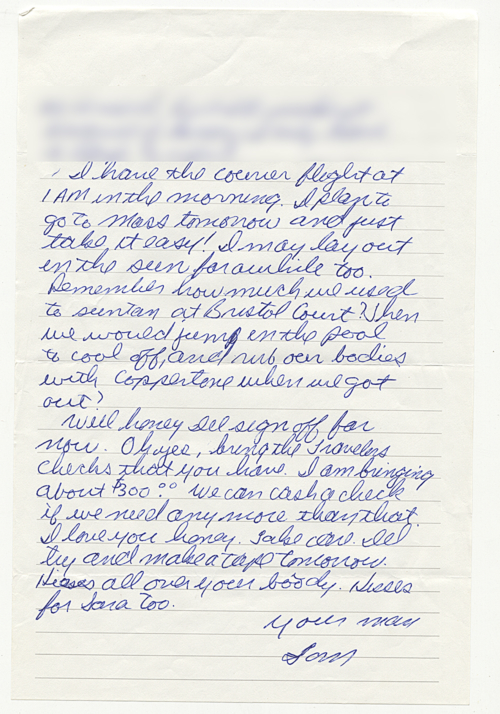

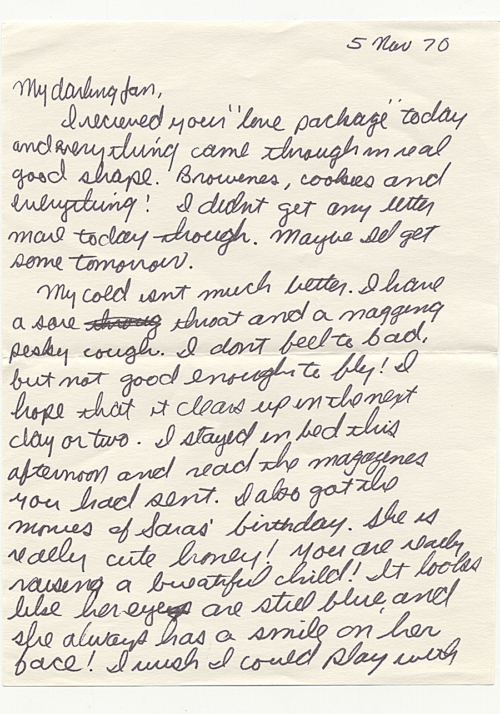

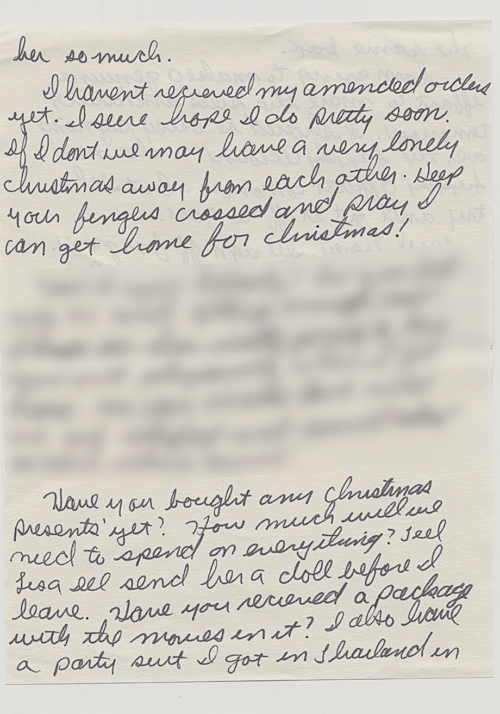

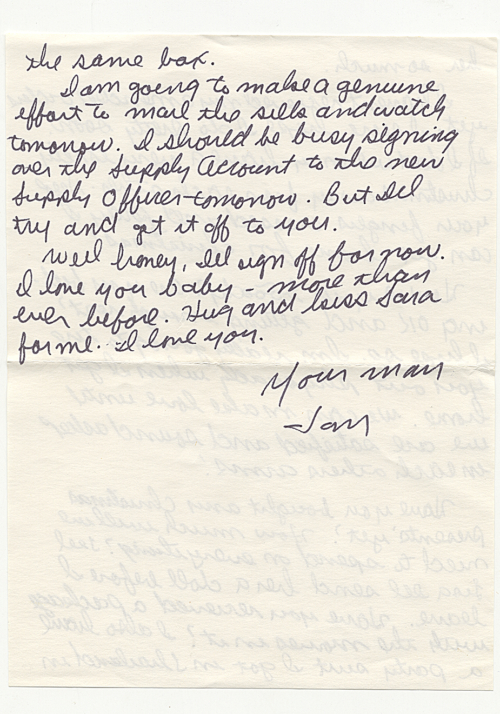

Letters Home

Tom Baca's correspondence letters to his wife during the war

More Veteran Profiles Below | Back to New Mexico & Vietnam War Page